|

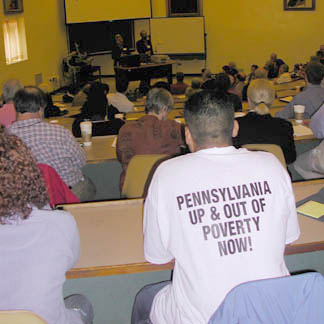

Editorial: This past Saturday at 9 a.m., over 200 political and community activists filed in to a large classroom at the law school of the University of Pennsylvania. Though most were Democrats, Mayor Street was not among them, nor were any sitting members of City Council, state legislators or representatives from Gov. Rendell’s office. But Tammy Gavitt was there. Gavitt, a member of Philadelphia NOW who is running for the PA House of Representatives in the 177th District, related a conversation she had recently with a campaign worker, “who I will call Joe.” “He asked me, ‘Does your organization accept money from candidates or do you accept promises of jobs?’ I said, ‘Neither.’ ‘I’m just learning the process,’ he told me. I told him, ‘What you’re learning is corruption.’” The room erupted in applause, as Gavitt had gotten to the heart of what brought this disparate group of Philadelphians together. This was the inaugural meeting of Neighborhood Networks, a reform effort co-founded by transit activist and West Mount Airy Neighbors president emeritus Marc Stier. The organization aims, as Gavitt said, to do no less than “change the landscape for people like me and other progressives who want to do good.” This means changing the pay-to-play culture that governs the political process, locally, statewide and nationally. It means empowering the poor and others who seek better political representation to force politicians to give them something real in return for their votes. It means returning politics to the neighborhood level, with street-level volunteers educating citizens on issues and candidates. It means bringing out the “inner liberal,” as Stier termed it, in well-meaning politicians who have had their progressive leanings “buried by the machine.” The frustration — and tentative sense of hope — of those alienated by the process was powerfully illustrated by Cheri Honkala of the Kensington Welfare Rights Union: “With Neighborhood Networks, gone will be the days when poor people will not be registered … when free t-shirts will determine an election … [when] election day is the number one day of employment for poor people … [when] drug dealers intimidate poor people [into not voting].” Ambitious goals, to be sure. But this group is not na´ve. Fed up with both Democrats and Republicans (some of the bitterest barbs flung by this liberal audience were at the liberal PAC MoveOn.org; one speaker ruefully summarized the Democrats’ current platform as “we’re not the other guy”), the group’s vision is to work within the existing city party structure of wards and committees to promote issues and provide a means for upstart reformers to get the kind of support and funds needed to mount a campaign. In the process, they hope to pull the Democratic Party back toward advocacy for the underprivileged and away from the temptations of the patronage system. The group has a long way to go before it can become a force in city or state politics. There are bylaws to work out, as well as decisions to be made on how to choose leaders and endorsements. But, as steering committee member and Mt. Airy resident Stan Shapiro pointed out, only a few thousand votes can change the course of an election. Local, grassroots work by a cadre of committed volunteers can make a difference. Just getting so many people together on a Saturday morning with limited publicity is a hopeful sign. Punning on the address of Penn’s law school, Stier called the gathering a “miracle on 34th Street.” Whether Neighborhood Networks can bring about the miracle of transforming entrenched politics remains to be seen.

James Sturdivant

|